Venezuela’s Sinister Turn

< < Go Back

Under Nicolás Maduro, a country that had been one of Latin America’s wealthiest is having its democratic institutions shredded amid rising poverty and corruption.

Almost two decades after Venezuela’s late president, Hugo Chávez, came to power in an electoral landslide, his country’s transformation seems to be taking an ominous new turn. A country that was once one of Latin America’s wealthiest is seeing its democratic institutions collapse, leading to levels of disease, hunger and dysfunction more often seen in war-torn nations than oil-rich ones.

Mr. Chávez’s successor, President Nicolás Maduro, has called for a National Constitutional Assembly to be elected on July 30 to draft a new constitution, in which ill-defined communal councils will take the place of Venezuela’s traditional governing institutions, such as state governments and the opposition-dominated Congress. The new assembly appears to be rigged to heavily represent groups that back the government.

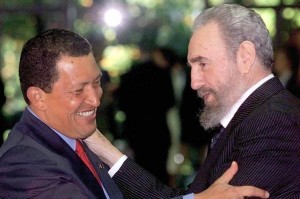

The Maduro government says that the new assembly will find a peaceful way forward for a country enduring an economic depression and standing on the brink of civil conflict. The government says it is building on the legacy of Mr. Chávez, a military man who vowed to fight corruption, dismantle the venal old political establishment and be a voice for millions of poor Venezuelans. But the opposition, which is boycotting the assembly vote, calls it a naked attempt to end democracy and turn the country into a Cuba-style communist autocracy. The government’s own attorney general calls the vote illegal.

The 545-member assembly, a modern-day soviet, would hold unlimited power while it writes a new governing charter, which could take years. Meantime, the assembly is widely expected to scrap next year’s presidential elections.

“This is the last battle for democracy in Venezuela,” says David Smilde, a Venezuela expert at Tulane University.

For the U.S., the prospect of a new Cuba sitting atop trillions of dollars of oil reserves is profoundly unpleasant. For the past decade, Venezuela has aligned itself with Russia, China, Iran and Syria. Whether it thrives or implodes, Mr. Maduro’s petrostate could cause far greater headaches to the U.S. and Latin America than isolated Cuba. An implosion could mean bigger shipments of cocaine to Central America and the U.S., as well as a massive increase in the current flow of tens of thousands of refugees already fleeing the country for the U.S., Colombia, Brazil and elsewhere. And a consolidation of power could let Mr. Maduro deepen his partnership with U.S. adversaries.

The Trump administration has criticized Mr. Maduro’s plans to change the constitution, urging “respect for democratic norms and processes.” The U.S. has called for Venezuela to free political prisoners, respect the opposition-controlled congress and “hold free and democratic elections.”

Mr. Maduro’s move has aggravated Venezuela’s political crisis. The opposition, sensing a do-or-die moment, plans to ramp up daily street protests. Some 80 people have died in such demonstrations in the past three months, and the president is unlikely to ease off on the tear gas, rubber bullets and water cannons.

“Maduro’s ultimate aim is to turn Venezuela into Cuba. And we will not accept being put in that cage,” says Julio Borges, the head of the opposition-dominated National Assembly.

“The government is desperate because they know the next presidential election will be their last,” says César Miguel Rondón, a popular radio host. When the host recently tried to leave Venezuela on a business trip to Miami with his family, he had his passport seized. “I’m a hostage in my own country,” he said.

By year’s end, Venezuela’s economy will have shrunk by nearly a third in the past four years—a plunge similar to Cuba’s after the fall of the Soviet Union, and one rarely seen outside of conflict zones. In a nation estimated to be sitting on as much oil as Saudi Arabia, it is common to see poor families rummaging through garbage for food, even as the wealthy pack nearby gourmet restaurants.

The so-called Bolivarian revolution has become less about ideology and more about money. Venezuelans often call it a “robolución” rather than a “revolución,” using the Spanish word for robbery. If Cuba is an ideologically motivated communist dictatorship, Venezuela is something different: as oil-rich as Saudi Arabia, as authoritarian as Russia and as corrupt as Nigeria.

In Cuba, the Castro dynasty has kept power despite decades of disastrous economic policies due to devotion to the charismatic Fidel, popular achievements such as universal free health care, ideological loyalty to Marxism, discipline enforced by security forces, and the nationalist frisson of facing off against the U.S. In Venezuela, aside from a similar devotion to Mr. Chávez, the glue that has held the regime together is simpler: oil-soaked corruption on an epic scale.

The government didn’t respond to requests for comment, but in the past, Mr. Maduro and other officials have dismissed accusations of corruption, economic mismanagement and repression as part of an “economic war” being waged by Venezuela’s private sector, in cahoots with the U.S., to destabilize and overthrow the socialist government.

As in many petrostates, oil accounts for 95% of Venezuela’s foreign-currency earnings. Since the government administers the oil, one sure way to get ahead is not by creating a new business but by getting close to the government to secure access to oil rents. Venezuelans call the enterprising class following this model “los enchufados”—the plugged-in ones.

The path to power in Venezuela is often said to run through the army and oil. Once in power, the populist Mr. Chávez went after the oil, eventually firing 19,000 employees of the state-run oil firm Petróleos de Venezuela to stack the company with his yes-men.

In the following years, oil prices rose sharply, and Mr. Chávez spent lavishly. He saved none of the windfall, ran large budget deficits even at peak-oil prices, raided the country’s rainy-day oil fund, and borrowed heavily, first from Wall Street and then from the Chinese and the Russians. He handed out billions of dollars worth of cut-rate oil to Cuba, Nicaragua and even Boston and London to show off Venezuela’s growing energy clout.

The number of government employees doubled, to five million, and spending skyrocketed. Printing so much money caused inflation, so the government set prices, sometimes below the cost of production. Companies that refused to sell at a loss were seized, aggravating shortages. Less local production made the country ever more reliant on imports.

But once the price of oil began to drop in 2014, Venezuela could no longer afford the imports, which have fallen from $66 billion in 2012 to about $15.5 billion this year. And there is little domestic industry left to pick up the slack.

“It is classic Latin American populism on steroids, and now we have the worst hangover in history,” said Juan Nagel, a Venezuelan economist living in Chile.

Unperturbed, the flamboyant leader focused on projects like changing Venezuela’s time zone by half an hour. He renamed the country the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. And to mark the shift in Venezuela’s political course, he changed the direction of a wild stallion on the country’s coat of arms, making the horse gallop left instead of right.

Corruption helps the government maintain political control.

“It’s a terrible economic model, but it’s great for politics and power,” says Asdrúbal Oliveros, a prominent Venezuelan economist.

Alberto Barrera, the author of a biography of Mr. Chávez who now lives in Mexico City, thinks that the time is fast approaching when he and the opposition may need to say goodbye to their hopes. “I wonder when I will wake up and realize, ‘They beat us.’ That it’s all over and the country I knew is gone,” he said.

More From The Wall Street Journal (subscription required):