from NCPA,

2/10/16:

Experts point to a variety of issues that likely caused the 2008 financial crisis, such as modern banking practices, unethical behavior or government policy. The available evidence suggests, however, that a convoluted interaction between the public sector and private sector business was the primary culprit.

This relationship created the subprime mortgage crisis, which caused the 2008 meltdown. Why is this crisis any different, though? After all, government action in private finance is not a new phenomenon.

Evolution of the Financial Industry. In response to a shortage of credit available to residents in low-income communities, Congress passed and President Jimmy Carter signed the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). The CRA promoted standardized lending practices for borrowers regardless of race, income or location and mandated that federally insured banks not engage in redlining, the refusal to extend credit to people living in particular locations. Government regulators used CRA as its authority to evaluate banks’ lending practices to ensure financial institutions did not deny credit to the areas they serve. The CRA proved to be a precursor for other future government intervention in the housing market.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the savings and loans crisis prompted further changes in regulation, government policy and banking procedures. Savings and loans associations (S&Ls), known as thrifts, served as a type of local financial institution specializing in savings deposits and consumer loans. The government also insured these associations to encourage investment and savings among fixed-income families and individuals. However, between rising inflation, government spending, and other economic factors in the 1970s and early 1980s, S&Ls found themselves with increased debt and decreased capital. Despite federal deposit insurance, many associations went under. And government deregulation policies that followed did little to recover investor money from the failed S&Ls. Federal guarantees for these institutions could not overcome the consequences of their collapse.

Meanwhile, the failure of these smaller, government-backed S&Ls precipitated a growth in larger financial institutions. The Gramm–Leach– Bliley Act (GLBA), also known as the Financial Services Modernization Act, passed Congress in November 1999. It legalized mergers between banks, insurance companies and securities firms previously outlawed by the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. After GLBA, large investment institutions grew into even larger corporate institutions. Several instances of corporate corruption at large, publically-held companies like Enron ‒‒ an American energy and commodities company found to have engaged in systemic accounting fraud in 2001 ‒‒ inspired regulatory action. In response, the federal government passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, which gave the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) ‒‒ the chief federal financial regulator ‒‒ new authority to detect and prevent systemic fraud at these massive financial institutions. These government regulatory powers were intended to prevent future fraudulent activity, protect the investor and ultimately promote the market’s financial stability.

This relationship created the subprime mortgage crisis, which caused the 2008 meltdown. Why is this crisis any different, though? After all, government action in private finance is not a new phenomenon.

Evolution of the Financial Industry. In response to a shortage of credit available to residents in low-income communities, Congress passed and President Jimmy Carter signed the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). The CRA promoted standardized lending practices for borrowers regardless of race, income or location and mandated that federally insured banks not engage in redlining, the refusal to extend credit to people living in particular locations. Government regulators used CRA as its authority to evaluate banks’ lending practices to ensure financial institutions did not deny credit to the areas they serve. The CRA proved to be a precursor for other future government intervention in the housing market.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the savings and loans crisis prompted further changes in regulation, government policy and banking procedures. Savings and loans associations (S&Ls), known as thrifts, served as a type of local financial institution specializing in savings deposits and consumer loans. The government also insured these associations to encourage investment and savings among fixed-income families and individuals. However, between rising inflation, government spending, and other economic factors in the 1970s and early 1980s, S&Ls found themselves with increased debt and decreased capital. Despite federal deposit insurance, many associations went under. And government deregulation policies that followed did little to recover investor money from the failed S&Ls. Federal guarantees for these institutions could not overcome the consequences of their collapse.

Meanwhile, the failure of these smaller, government-backed S&Ls precipitated a growth in larger financial institutions. The Gramm–Leach– Bliley Act (GLBA), also known as the Financial Services Modernization Act, passed Congress in November 1999. It legalized mergers between banks, insurance companies and securities firms previously outlawed by the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. After GLBA, large investment institutions grew into even larger corporate institutions. Several instances of corporate corruption at large, publically-held companies like Enron ‒‒ an American energy and commodities company found to have engaged in systemic accounting fraud in 2001 ‒‒ inspired regulatory action. In response, the federal government passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, which gave the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) ‒‒ the chief federal financial regulator ‒‒ new authority to detect and prevent systemic fraud at these massive financial institutions. These government regulatory powers were intended to prevent future fraudulent activity, protect the investor and ultimately promote the market’s financial stability.

Government Policy. The federal government’s increased intervention in the marketplace in the years before and after the 2008 financial crisis contributed to and then deepened the crisis.

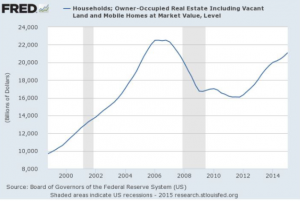

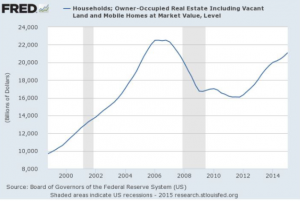

Cause 1: Tax Policy Fueled the Housing Bubble. The tax deduction for home mortgage interest remains one of the most popular item for taxpayers. Though the government phased out deductions for interest on car loans and credit cards in the early 1990s, the home mortgage interest deduction remained. This policy led to an increase in the number of financial institutions offering home equity loans, advertised as an option for paying off expensive, nondeductible consumer debt. The Clinton administration followed that in 1997 by passing a tax bill which gave homeowners the right to take up to $500,000 in profits on their home tax free. The policy fueled the housing bubble and caused a significant increase in home values [see Figure I].

Cause 2: Land Use Regulation Drove an Artificial Rise in Home Prices.

Cause 3: Low-quality Loans at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Cause 4: Government Policy Encouraged Poor Mortgage Underwriting Standards.

Cause 5: Derivatives Spread Bad Loans Across the Marketplace.

Cause 6: Existing Regulation Missed the Crisis and Inspired Regulatory Overcorrection.

Cause 7: Federal Reserve Policies.

Banking Strategies. Major adjustments to banking practices in the financial sector leading up to 2008 and the growth of large institutions represent a second category of potential causes behind the financial crisis.

Cause 8: Structural Changes in the Banking Industry. In 2002, Donald D. Hester, professor of economics at the University of Wisconsin, said that banks had increasingly discarded their “traditional mode of financing loans and investments with deposits they collect,” and had become brokers for loan origination. These bankers-turned-brokers used “securitization to lodge” mortgages with less-informed investors, which made the products more “vulnerable to losses.” These products only became more complicated as vehicles for investments

Cause 9: Securitization Obscured Investment Vulnerabilities.

Cause 10: Escalation in

Home Prices and Interest on Loans Sparked Foreclosures.

Cause 11: Change in Bank Capital Requirements.

Cause 12: Large Amount of Loans to Investors not Homeowners.

Cause 13: Financial Institutions Allowed to Hold Much More Debt than Capital.

Cause 14: Mark-to-market Accounting Created False Asset Values.

Moral Hazards.The final category of causes for the financial crisis involves public and private sector corruption leading up to and during the 2008 meltdown.

Cause 15: Appraisal Fraud. The FBI received reports of more than 35,000 cases of mortgage fraud totaling almost $1 billion in losses in 2006, up from 7,000 reports in 2003. One fraud technique, called the “foreclosure rescue,” involved companies that targeted homeowners facing foreclosure with a temporary refinancing or sale plan. In short, the homeowner remained in the home and made larger monthly payments to the refinancers. But if the owner defaulted, he or she lost their home entirely, and the scam artist then sold the home and kept the equity.

Cause 16: Fraud by the Borrower. Some borrowers employed a technique known as “silent seconds,” or not disclosing to the first lien holder that the alleged down payment was borrowed from another lender. In 2006, this fraudulent practice accounted for 25 percent of subprime mortgages and 40 percent of Alt-A mortgages.

Cause 17: Fraud and Greed in the Lending Process.

Mortgage brokers and nonbank mortgage companies such as Ameriquest routinely lied on mortgage loan applications, misstating the income of borrowers. Meanwhile, an emphasis on fee-based commissions became a new business model, according to one observer, which debased the process from drafting quality loans to collecting fees for processing products or inventory.

Cause 18: Corruption and Poor Performance at Bond Rating Agencies.

Cause 19: Increase in Lobbying.

Cause 20: Lack of Trust in the Market.

Conclusion. There is no shortage of alleged causes for the 2008 financial crisis. From government interference and public sector mismanagement to instances of corruption in both the private and public sectors, the list of explanations goes on without end. Yet, the exact origins of the crisis are not elusive. By grouping the major and reasonable arguments into three digestible categories, the roots of the financial crisis become clearer: increased government intervention in the marketplace, particularly the mortgage business, and changes in banking strategies together planted the seeds for financial ruin and created an environment ripe for corruption. Although the blame seems widespread, we can isolate the root causes. The priority now is to use this evidence to ensure history does not repeat itself.

More From NCPA: