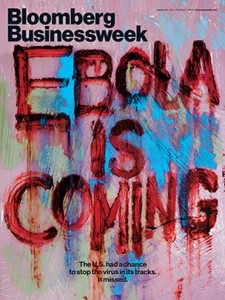

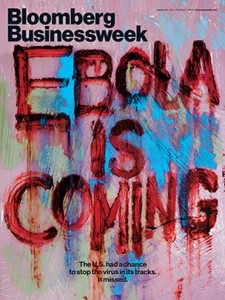

By Brendan Greeley and Caroline Chen,

from Bloomberg BusinessWeek,

9/24/14:

In July, Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol, both American medical workers in Liberia, became stricken with Ebola hemorrhagic fever after treating dozens suffering from the disease, which has a mortality rate of 50 percent to 90 percent. They were rushed doses of an experimental cocktail of Ebola antibodies called ZMapp. Cared for in a special ward at Emory University in Atlanta, they recovered within the month.

Mapp Biopharmaceutical, the San Diego company that developed ZMapp, is also in a way a White House project. It’s supported exclusively through federal grants and contracts that go back to 2005.

It’s too early to say whether ZMapp was vital to the Americans’ survival. There were a limited number of doses available. Mapp ran out after having given doses to the two Americans, a Spanish priest, and doctors in two West African countries, although it declined to say how many.

Since appearing in Guinea in December, Ebola has spread to five West African countries and infected 5,864 people, of which 2,811 have died, according to the World Health Organization’s Sept. 22 report. This number is widely considered an underestimate. The CDC’s worst-case model assumes that cases are “significantly under-reported” by a factor of 2.5. With that correction, the CDC predicts 21,000 total cases in Liberia and Sierra Leone alone by Sept. 30.

A confluence of factors has made it the biggest Ebola outbreak yet. For starters, West Africa has never seen Ebola before; previous outbreaks have mainly surfaced in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Central Africa. The initial symptoms of Ebola—fever, vomiting, muscle aches—are also similar to, and were mistaken for, other diseases endemic to the region, such as malaria.

Then, when officials and international workers swept into villages covered head to toe and took away patients for isolation, some family members became convinced that their relatives were dying because of what happened to them in the hospitals. They avoided medical care and lied to doctors about their travel histories. Medical staff at local hospitals became scared and quit their jobs. Aid workers trying to set up isolation units or trace infected people’s contacts were attacked by angry villagers. With these countries short on resources, staff, medical equipment, and basic understanding of the disease, Ebola took hold and spread.

Some say, the Ebola crisis won't end without military intervention.

There have been a number of admirable and vigilant responses, from local doctors and emergency workers to nongovernmental organizations such as Doctors Without Borders. Foreign governments have so far pledged about a third of the $988 million the United Nations says is needed to fight the epidemic. On Sept. 16, the Obama administration announced plans to send 3,000 military personnel to assist with shipping and distribution of medical equipment and supplies. The Americans will also help build treatment centers and train health-care providers in the region.

Could a large stockpile of ZMapp have halted the spread of Ebola? No one can say. What’s certain is that the U.S. government hasn’t done a good job taking the idea behind ZMapp and turning it into a treatment.

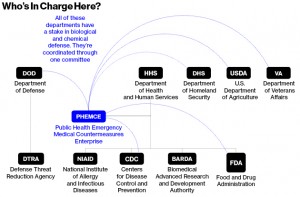

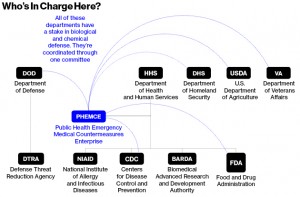

In the 1990s, after revelations of the Soviet biological and chemical weapons programs and the 1995 sarin gas attack in the Tokyo subway, the U.S. handed its defensive drugmaking to the Pentagon. After 2001, the Pentagon budget for biological and chemical defense rose from $880 million to $1.12 billion. Since then, roughly a third of its total budget, about $3.9 billion, has been designated for a list of “biological threat agents.” The list is classified, but it now numbers 18, according to a 2014 analysis by the U.S. Government Accountability Office. Ebola is almost certainly on this list and likely near the top. The Soviet Union had an Ebola program, and Aum Shinrikyo, the cult that released the sarin gas in Tokyo, sent doctors in 1993 to what’s now the Democratic Republic of the Congo on an unsuccessful mission to get an Ebola sample.

Then, because the 2001 anthrax attacks on the Capitol in Washington were directed at civilians, the Department of Health and Human Services launched a parallel track in biochemical defense. Soon, the HHS began keeping its own list of biological threats. Over the next two years, the budget at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the HHS, jumped from $2.04 billion to $3.7 billion. Two separate arms of the federal government, with a $5 billion annual budget between them, now were focused on the same set of problems but not talking to each other well. And neither was accomplishing what was needed most: producing drugs.

By 2006 the White House became aware of an inefficiency. NIAID’s budget went to sponsor basic research at university and commercial labs, but the agency didn’t move its ideas out of the lab, into trials, and through the FDA approval process. The Pentagon’s program also “never got enough money to be a pharmaceutical company".

“For things like Ebola, there is no clear buyer other than the government,” says Thomas Inglesby, the director of the Center for Health Security at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center who’s advised three White Houses on biosecurity issues. Normally, he notes, market potential “pulls” a drug forward. With relatively rare tropical diseases, “you basically have to start and finish that process” within the government, “because there is no other buyer in the world.”

Mapp Biopharmaceutical was looking for more money. Founded in 2003, the company has nine employees (as of Aug. 5) and no external investors. For about a decade, it’s taken an approach to Ebola that had been largely abandoned. Rather than develop a vaccine, which triggers the body to create its own antibodies—defenses against a virus—Mapp worked to develop monoclonal antibodies, a ready-made supply that can be introduced into the body as a therapy after infection. The company didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Mapp had been funded through grants from NIAID, the civilian agency that did only basic research. While NIAID continued to fund Mapp until 2013, the grants were small, generally around $1 million a year, enough to keep the lights on but not enough to get ZMapp into clinical trials.

... the 2011 presentation concluded, the agency lacked “translational S&T project management discipline,” which is a bureaucratic way of saying that there was no way to take ideas and move them down the long path toward a drug approved by the FDA for production or technology ready for the Pentagon to deploy.

Mapp received a commitment from DTRA in February 2011 for MB-003, ZMapp’s predecessor. This means that the antibody had been deemed a worthy idea but needed to go through a review process before any actual money could be disbursed to develop it. And that’s when the ZMapp program really stalled.

... people with pharma experience, she says, in turn failed to show the patience necessary to work in any government agency. “Frequently, what [government contracting officers] were requesting was ridiculous,” she says, “but you know what, you just do it.” One trick to federal contracting, she explains, is to know when not to fight.

It’s still uncertain how effective ZMapp is, because only a handful of people have taken it. But doctors would have had a better idea if it hadn’t been stuck in the federal bureaucracy for four years. The drug’s path through the research labs of the Washington-Baltimore corridor shows that the federal government still isn’t good at producing drugs. Barda needs money. DTRA can’t move quickly. And the U.S., until now, hasn’t made Ebola a priority. “That’s why we don’t have an Ebola countermeasure,” says Kadlec. “We failed to invest enough dollars to have it mature.”

Every outbreak will make every administration look feckless and incompetent. But the U.S., at the very least, needs to admit to itself that to improve readiness, it needs to function like a drugmaker—and be good at it. “As long as there’s not sufficient money to address every one of the targeted diseases,” says Senator Burr, “it’s going to force the system to make a decision based on what’s the greatest threat today.”

More From Bloomberg BusinessWeek: