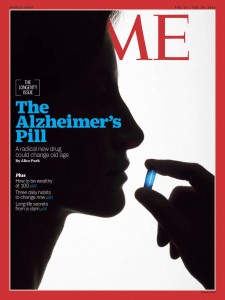

The Alzheimer’s Pill

< < Go Back

A radical new approach to treating the fearful disease is showing promise.

Dr. Frank Longo isn’t the kind of guy who chokes up easily. The pre-eminent neurologist is better known for his professional stoicism and scholarly approach to the devastation he sees weekly in his Alzheimer’s patients.

As chairman of the department of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford, Longo knows how destructive Alzheimer’s can be. He specializes in memory disorders and regularly sees patients whose brains are slowly scrambling. In recent years he’s grown frustrated. Alzheimer’s was first discovered in 1906, which means doctors have had a century to peel away the disease’s molecular layers and search for a cure.

My biggest frustration is that we’ve cured Alzheimer’s in mice many times. Why can’t we move that success to people?” Longo says.

(He’s referring to numerous promising compounds that have eliminated the amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s in animals.) If the ongoing human trials continue to progress the way he hopes, Longo’s drug, called LM11A-31, could be a critical part of finally making that happen. But that’s still a big if.

To further develop the drug for patients, Longo created a company, PharmatrophiX, which conducted the first phase of clinical trials required for all pharmaceuticals; the drug was deemed safe and caused minimal negative side effects. Now, it’s in phase II, when the drug will be tested in people with the disease, to see if it ameliorates their symptoms. If the trial goes the way Longo and other leading Alzheimer’s experts expect, LM11A-31 will then be on its way to being approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Longo’s drug is noteworthy because of the promise it showed in those mouse studies and because it’s been shown to be safe in humans. But what really sets it apart is that it attacks Alzheimer’s in an altogether different way than the drugs that preceded it.

For decades, scientists have pursued a cure with a nearly single-minded focus on how to treat the disease: by trying to get rid of the hallmark feature of Alzheimer’s, which is sticky, insidious protein plaques of amyloid that they have fought so well in mice. If they could get rid of that in humans too, the thinking went, they could get rid of the disease–or at least lessen its severity. But LM11A-31 doesn’t directly attack amyloid at all.

“We’re agnostic about what is actually causing Alzheimer’s,” Longo says, referring to those protein plaques. “Most people are working at the edges of the problem, but we’re going right after the core of it.” LM11A-31 isn’t designed to chase after every last clump of amyloid and wipe it away. The core, in this case, is simply to keep brain cells strong, protected against neurological onslaughts, whether they’re the effects of amyloid or other factors involved in Alzheimer’s. It’s a much less orthodox approach, but–as Longo’s emotion suggests–if it works, it could be a game changer.

More From TIME Magazine: