Europe’s Empty Churches Go on Sale

< < Go Back

Hundreds of Churches Have Closed or Are Threatened by Plunging Membership, Posing Question: What to Do With Unused Buildings?

Two dozen scruffy skateboarders launched perilous jumps in a soaring old church building here on a recent night, watched over by a mosaic likeness of Jesus and a solemn array of stone saints.

This is the Arnhem Skate Hall, an uneasy reincarnation of the Church of St. Joseph, which once rang with the prayers of nearly 1,000 worshipers.

It is one of hundreds of churches, closed or threatened by plunging membership, that pose a question for communities, and even governments, across Western Europe: What to do with once-holy, now-empty buildings that increasingly mark the countryside from Britain to Denmark?

The Skate Hall may not last long. The once-stately church is streaked with water damage and badly needs repair; the city sends the skaters tax bills; and the Roman Catholic Church, which still owns the building, is trying to sell it at a price they can’t afford.

“We’re in no-man’s-land,” says Collin Versteegh, the youthful 46-year-old who runs the operation, rolling cigarettes between denouncing local politicians. “We have no room to maneuver anywhere.”

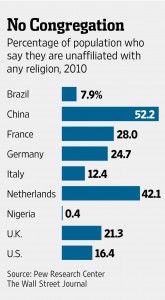

The closing of Europe’s churches reflects the rapid weakening of the faith in Europe, a phenomenon that is painful to both worshipers and others who see religion as a unifying factor in a disparate society.

“In these little towns, you have a cafe, a church and a few houses—and that is the village,” says Lilian Grootswagers, an activist who fought to save the church in her Dutch town. “If the church is abandoned, we will have a huge change in our country.”

Trends for other religions in Europe haven’t matched those for Christianity. Orthodox Judaism, which is predominant in Europe, has held relatively steady. Islam, meanwhile, has grown amid immigration from Muslim countries in Africa and the Middle East.

The number of Muslims in Europe grew from about 4.1% of the total European population in 1990 to about 6% in 2010, and it is projected to reach 8%, or 58 million people, by 2030, according to Washington’s Pew Research Center.

For Christians, a church’s closure—often the centerpiece of the town square—is an emotional event.

When they close, towns often want to re-create the feeling of a community hub by finding important uses for these historic buildings. But the properties are usually expensive to maintain—and there is a limit to the number of libraries or concert halls a town can financially support. So commercial projects often take the space.

The Church of England closes about 20 churches a year. Roughly 200 Danish churches have been deemed nonviable or underused. The Roman Catholic Church in Germany has shut about 515 churches in the past decade.

But it is in the Netherlands where the trend appears to be most advanced. The country’s Roman Catholic leaders estimate that two-thirds of their 1,600 churches will be out of commission in a decade, and 700 of Holland’s Protestant churches are expected to close within four years.

“The numbers are so huge that the whole society will be confronted with it,” says Ms. Grootswagers, an activist with Future for Religious Heritage, which works to preserve churches. “Everyone will be confronted with big empty buildings in their neighborhoods.”

The U.S. has avoided a similar wave of church closings for now, because American Christians remain more religiously observant than Europeans. But religious researchers say the declining number of American churchgoers suggests the country could face the same problem in coming years.

More From The Wall Street Journal (subscription required):