From 1889 to 2014, Political Parallels Abound

< < Go Back

Hope in History? Past Is Prologue in Problems and Progress.

The country is narrowly divided between Democrats and Republicans, with a bright line separating red states and blue states. Rapid technological change is sowing economic unease. A wave of immigration adds to the unsettled feeling. Anger rises over income inequality, which is discussed in popular books. Put it all together and the result is a rising tide of populist sentiment.

A description of today’s political picture? Well, yes.

But that also happens to describe the political lay of the land that existed on July 8, 1889, the day The Wall Street Journal was born 125 years ago. In fact, the similarities between the situation then and now are uncanny.

Yet while the parallels are fascinating, they aren’t the most important part of this picture. More instructive is what unfolded in the decade or so that followed.

The two major parties—then as now the Democrats and the Republicans—adapted and evolved. A populist third party arose briefly, but the major parties found ways to absorb the sentiments fueling the populist tide without adopting its most extreme elements. The unrest of 1889 gave way to a remarkable period of economic and political reforms that left the political system changed but, ultimately, stronger and more stable.

Is that what lies ahead now?

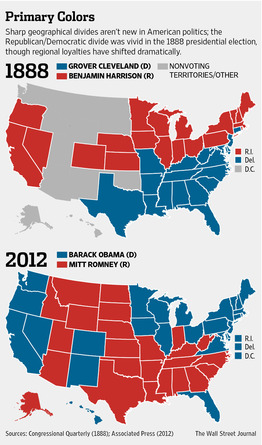

The political divides of 1889 were well captured by the previous year’s presidential election. The country was so evenly split between the two parties that Democrat Grover Cleveland won the popular vote, but Republican Benjamin Harrison won the presidency by winning the Electoral College vote.

A map of the outcome of that election by state shows a red/blue divide just as stark as today’s—though, as Mr. Kazin notes, the geographic bases of the two parties have been “almost reversed” since. In 1888, the South was a solid blue bloc of Democratic states and the North a similarly monochromatic red bloc of Republican states.

Beneath the political divide coursed economic nervousness. The industrial revolution was bringing powerful and efficient machinery to factories, leaving many workers uneasy about their jobs. A giant wave of immigrants—an estimated 11 million from 1870 to 1899—was driving the economy forward but making established workers nervous, especially in the cities where migrants gathered.

Above all, suspicion and anger over the power of financial institutions and big businesses—particularly industrial conglomerates—was growing, and giving rise to populist sentiments. Indeed, a Populist Party was formed in 1891. It became powerful enough in just one year that in 1892 it won three governors’ races and reaped a million votes in the presidential election that brought the Democrats’ Grover Cleveland back to power.

But then both established parties began to adapt and co-opt the populist sentiment. In 1896, Democrats nominated William Jennings Bryan, a fiery foe of the gold standard and the financial interests supporting it. He lost, but his rise left the Populist Party little reason to exist separately. A progressive movement also took root in the Republican Party, propelled by politicians such as Wisconsin Gov. “Fighting Bob” LaFollette, and ultimately by the trust-busting Teddy Roosevelt, who became president upon the assassination of William McKinley in 1901.

The populists’ most radical ideas—nationalizing banks, railroads and telegraph companies, for example—were discarded. But the movement helped spur a period of reforms, including ballot initiatives, secret ballots, direct election of senators and the adoption of a progressive income tax. Political ferment wasn’t over. Teddy Roosevelt broke away from the Republicans to form a progressive party in 1912. But the system worked; it responded to the most sensible of the sentiments at the grass roots.

Can the system turn political discontent into broader positive change? Today, we know this: It did so once before.

More From The Wall Street Journal (subscription required):