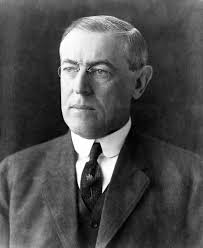

Woodrow Wilson’s Great Mistake

< < Go Back

by Jim Powell,

For a long time, Americans have been branded as “isolationists” guilty of “appeasement” when they question the wisdom of starting or entering another foreign war.

The terms “isolationist” and “appeasement” are used to link today’s noninterventionists to the political leaders who, during the 1930s, did nothing to stop Hitler early on, when that might have been easy. Ever since then, starting or entering wars has been justified by claiming that the present situation is analogous to the threat from Nazi Germany and requires force.

The first problem with such a scenario is that Hitler’s rise to power owed much to a prior war: World War I, which was supposed to end war.

British prime minister David Lloyd George reportedly remarked, “This war, like the next war, is a war to end war.” Journalist Walter Lippmann said “the delusion is that whatever war we are fighting is the war to end war.”

Precisely because France and Britain entered World War I and were devastated — which none of the political leaders seem to have anticipated — people in those countries lacked the will for another war. They had also been lied to repeatedly by their political leaders, and they weren’t interested in going through that again. As far as Americans were concerned, the greed and hypocrisy of World War I belligerents discredited the idea of doing good by going to war, which is why Americans wanted nothing to do with another foreign war. It was because pro-war people lost their credibility during World War I that nobody responded when alarms were sounded about Hitler during the 1930s.

If popular sentiment now generally opposes starting or entering foreign wars, the people who deserve considerable credit are those “internationalists” who promote participation in wars that go wrong. Often there are terrible unintended consequences, because wars are the most costly, volatile, unpredictable, and destructive human events.

World War I was probably history’s worst catastrophe, and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson was substantially responsible for unintended consequences of the war that played out in Germany and Russia, contributing to the rise of totalitarian regimes and another world war.

If the U.S. had stayed out of the war, it seems likely there would have been some kind of negotiated settlement. Neither the Allied Powers (France, Britain, Russia, Italy, Japan, and several smaller states) nor the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria) would have gained everything they wanted from a negotiated settlement. Both sides would have complained. But a catastrophe would have been less likely after a negotiated settlement than after vindictive terms were forced on the losers.

French and British generals squandered the youth of their countries by ordering them to charge into German machine-gun fire, and they wanted to command American soldiers the same way.

On April 2, 1917, when Wilson went before Congress to seek a declaration of war, he wasn’t trying to protect the United States from an attack or imminent attack, although there had been provocations. His stated aim was to destroy German autocracy. He urged “the crushing of the Central Powers.” He famously promised that the world “would be made safe for democracy.”

The U.S. played a significant military role only during the last six months of the war, but that was enough to change history — for the worse. By entering the war on the side of the French and British, Wilson put them in a position to break the stalemate, win a decisive victory, and — most important — force vindictive surrender terms on the losers.

The French and British bribed Italy to enter the war on their side by signing the secret Treaty of London (April 26, 1915) that promised Italy war spoils in Austria-Hungary, the Balkans, Asia Minor, and elsewhere — and the Italians wanted it all. They were outraged to find that the French and British planned on giving them little. The Japanese demanded Chinese territory and a statement affirming racial equality, and while they didn’t get those things, they ended up receiving German assets in China’s Shantung province, including a port, railroads, mines, and submarine cables.

The vindictive surrender terms, made possible by American entry in the war and enshrined in the Treaty of Versailles, triggered a dangerous nationalist reaction. Hitler was able to recruit several thousand Nazis. Allied demands for reparations gave Germans incentives to inflate their currency and pay the Allies with worthless marks. The runaway inflation wiped out Germany’s middle class, and Hitler recruited tens of thousands more Nazis.

American entry in World War I helped produce another terrible consequence: the November 1917 Bolshevik coup in Russia. France and Britain had to know they were playing with fire when they pressured the Russians to stay in the war so that German forces would continue to be tied up on the Eastern Front. The last thing France and Britain wanted was for Russia to make a separate peace with Germany and thereby enable the Germans to transfer forces to the Western Front.

Following the spontaneous revolution and abdication of the czar in March 1917, Wilson authorized David Francis, his ambassador to Russia, to offer the Provisional Government $325 million of credits — equivalent to perhaps $3.9 billion today — if Russia stayed in the war. The Provisional Government was broke, and it accepted Wilson’s terms: “No fight, no loans.”

Thanks to Wilson’s misguided policies, the Bolshevik coup led to seven decades of Soviet communism. Historian R. J. Rummel estimated that almost 62 million people were killed by the Soviet government. He estimated that all 20th-century communist regimes killed between 110 million and 260 million people.

Nothing Wilson did could compensate for the colossal blunder of entering World War I. He claimed his League of Nations would help prevent future wars, but charter members of the League of Nations were most of the winners of the war and their friends — countries that hadn’t been fighting each other. They vowed to continue not fighting each other. Member nations agreed to join in defending any of them that might be attacked, which meant that the league was another alliance. An attack on one member nation would lead to a wider war. The World War I losers weren’t members.

Wilson’s admirers tend to blame postwar troubles on Republicans in Congress who refused to support his beloved League of Nations. Wilson’s arrogance toward Congress and his refusal to compromise had a lot to do with that. He failed to recognize that he couldn’t control his allies, he couldn’t control the losers, and he couldn’t control Congress. World War I should remind us that the consequences of war are extremely difficult to predict and often impossible to control. The world would have been better off if America had stayed out of that war and pursued a policy of armed neutrality.

More From CATO Institute: