China Has Already Tried Democracy. Or Has It?

< < Go Back

China has tried your form of government and found it wanting.

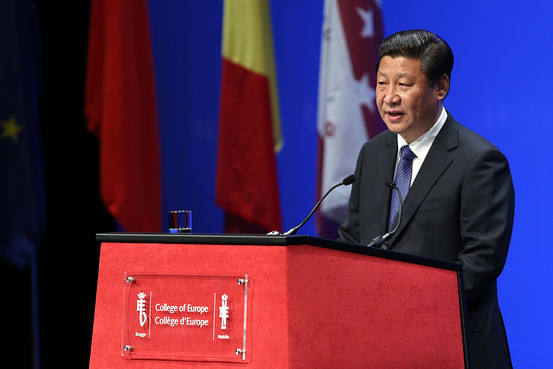

That was the message delivered by Chinese President Xi Jinping during an expansive address at the College of Europe in Bruges, Belgium, this week that capped off his first visit to Western Europe as China’s top leader.

In a speech littered with allusions to classical Chinese texts and other adornments intended to drive home the message that China is unlike any other country, Mr. Xi told the assembled crowd that the world’s most populous nation had considered virtually every form of government from constitutional monarchy and imperial restoration to parliamentary and multiparty democracy.

“We considered them, tried them. None worked,” China’s leader said.

He went on to argue for a sort of political terroir using a metaphor taken from “Yanzi’s Spring and Autumn Annals,” a collection of stories about wise and well-traveled 5th century B.C. official Yan Ying.

“I hear the oranges grown south of the Huai River are true oranges,” Mr. Xi said, quoting a speech Yan Ying gave to the King of Chu. “Once transplanted north of the river, they become bitter oranges. The leaves look similar, but they differ widely in taste. Why is that? It’s because the water and soil are not the same.”

Few would argue that political systems, like agricultural products, differ from place to place. Take Germany and Italy, two parliamentary countries that produce politics as distinctly flavored as their wines.

But what about Mr. Xi’s claim that China has given parliamentary and multiparty systems a fair shake?

John Delury, a China historian at Yonsei University, calls it “a bit of a stretch.”

As Mr. Delury documented in “Wealth and Power,” a recent book about 20th century Chinese political thinkers that he co-wrote with veteran China watcher Orville Schell, China did indeed go through a period of political experimentation beginning with the fall of the Qing Dynasty. A democratic Republic of China was established shortly after the dynasty fell in 1911 but essentially crumbled after its president, Gen. Yuan Shikai, declared himself emperor of a new dynasty in 1915.

“The only true nationwide election ever held took place in 1913,” Mr. Delury writes in an email. In that election, only men over the age of 21 who were educated or owned property were allowed to vote. They voted for electors, who then picked delegates to the two-house National Assembly. Delegates later re-elected Gen. Yuan, who had earlier taken over the provisional presidency from Sun Yat-sen.

While he may have exaggerated China’s experience with democracy, Mr. Xi was accurate in describing the “chameleonic quality” of the country’s recent political history, according to Mr. Delury. For much of the past hundred years, the historian says, China has been “desperately changing colors to find one that let it blend into the modern family of nations as a strong, prosperous and respected ‘great power.’”

More than devotion to any one political ideology, it is the desire to regain its former glory – to be wealthy and powerful – that has driven change in China in the last century, Messrs. Delury and Schell argue in their book.

Mr. Xi seems to be well aware of that dynamic. Since coming to power, he has repeatedly sought to portray the Communist Party’s reform efforts as part of a project of “national rejuvenation.”

More From The Wall Street Journal (subscription required):