Skid Roe

< < Go Back

By James Taranto,

What accounts for declining abortion rates?

“The abortion rate in the United States dropped to its lowest point since the Supreme Court legalized the procedure in all 50 states, according to a study suggesting that new, long-acting contraceptive methods are having a significant impact in reducing unwanted pregnancies,” the Washington Post reports, leaping to conclusions right in the lead paragraph.

The impulse behind that leap is understandable. Journalists are attracted to cause-and-effect explanations because they make storytelling easier, and in this case the causal explanation bolsters the cause of the group doing the study: the Alan Guttmacher Institute, research arm of Planned Parenthood.

Guttmacher’s data, we should note, are generally respected even by those who oppose Planned Parenthood’s agenda. But the singular of “data” is not “anecdote,” which is to say that changes in aggregate numbers like the abortion rate are generally the result of multiple causes, which may compound or offset each other. One should beware of simple explanations.

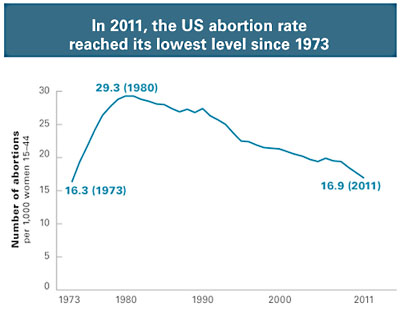

There’s no doubt the bottom-line finding is dramatic. In 2011, the year for which Guttmacher has just finalized and released its data, the abortion rate–defined as the number of abortions per 1,000 reproductive-age females (15-44)–was 16.9. The last time it was lower was in 1973, the year the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade, when it was 16.3. And that number, the Post piece argues, might have been understated: “Many abortions were still taking place underground and off the books at that time.” If one could account for illegal abortions, it’s conceivable the rate would be lower in 2011 than in 1973.

The study’s author, the Post reports, “suggested that one factor was greater reliance on new kinds of birth control, including intra-uterine devices such as Mirena, which can last for years and are not susceptible to user error like daily pills or condoms.” The study itself cites data suggesting that “long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods have begun to displace shorter term methods among women using contraceptives, especially those younger than 25.”

The abortion ratio–whose denominator is pregnancies (excluding miscarriages) rather than women–has also been declining, though more slowly than the rate. According to the Guttmacher study, the abortion rate fell to 16.9 in 2011 from 26.3 in 1991, a 36% drop; during the same period, the ratio fell 23%, to 21.2 from 27.4.

According to our back-of-the-envelope calculations, that reflects a decline in the pregnancy rate, to 8% from 9.6%, which would be consistent with improvements in contraception or more diligence in their employment. But other factors could also be at work, such as changes in sexual behavior or in the age distribution within the 15-44 female population.

One factor both the Post piece and the study cite is “the economy,” meaning the recession that began in late 2007 and the slow recovery that has followed.

One difficulty with the explanations discussed so far is that they involve recent technological and economic trends. Thus they cannot explain the long-term decline in the abortion rate, which is quite clear in the chart that accompanies the Post piece. The rate climbed steadily in the middle and late 1970s before peaking at 29.3 in 1980. The trend has been steadily downward ever since and was especially sharp during the booming 1990s.

Abortion opponents have a theory for that, the Post reports:

– They credit new technologies that allow people to better observe what happens in the womb even at the earliest stages of pregnancy.

– “This is a post-sonogram generation,” said Charmaine Yoest, president of Americans United for Life, the group behind many of the new state limits on abortions. “There is increased awareness throughout our culture of the moral weight of the unborn baby. And that’s a good thing.”

Which brings us to our pet theory, the Roe Effect. We argue that Roe v. Wade had the unanticipated political consequence of elevating the topic of abortion and polarizing public opinion around it and the unanticipated demographic consequence of reducing fertility unevenly and thereby intergenerationally diminishing support for abortion, as well as the proclivity to have abortions. In other words, the women deciding whether to have abortions now are disproportionately the daughters of women who opposed abortion. Of course parents don’t always convince their offspring of their views, but surely they have some influence in the aggregate.

One explanation Guttmacher discounts is what the Post calls a “recent wave of state laws restricting access to abortion.” Most of these were not yet in effect by 2011, according to the Post, but “those restrictions will surely have an impact on the numbers going forward, said Rachel K. Jones, a senior researcher at Guttmacher and lead researcher on the paper.”

More From The Wall Street Journal (subscription required):