Wanted: Jobs for the New ‘Lost’ Generation

< < Go Back

Five years after the 2008 crisis, younger adults still struggle to find work.

Derek Wetherell is stuck. At 23 years old, he has a job, but not a career, and little prospect for advancement. He has tens of thousands of dollars in student debt, but no college degree.

Mr. Wetherell is a member of a lost generation, a group that is only now beginning to gain attention of many economists and employment experts. From Oakland to Orlando—and across the ocean in Birmingham and Barcelona—young people have come of age amid the most prolonged period of economic distress since the Great Depression.

“This has been for quite a while now a hostile environment for young people,” said Paul Taylor, executive vice president of the Pew Research Center, which has studied the impact of the recession on young people. “This is all they’ve really known.”

The financial crisis that struck five years ago this month opened up a sinkhole in the U.S. economy that swallowed Americans of all ages and backgrounds. Retirees lost life savings. Families lost homes. Millions of Americans lost their jobs.

The financial crisis that struck five years ago this month opened up a sinkhole in the U.S. economy that swallowed Americans of all ages and backgrounds. Retirees lost life savings. Families lost homes. Millions of Americans lost their jobs.

Five years later, that hole is being filled in, however slowly. The unemployment rate is down to 7.3% amid slow, steady job growth.

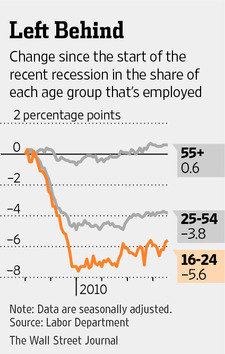

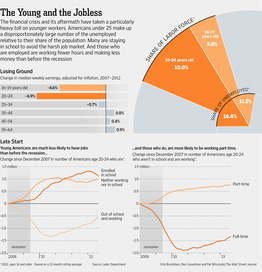

But the recovery has left many young people behind. The official unemployment rate for Americans under age 25 was 15.6% in August, down from a peak of nearly 20% in 2010 but still more than 2½ times the rate for those 25 and older—a gap that has widened during the recovery. Moreover, the unemployment rate ignores the hundreds of thousands of young people who have taken shelter from the weak job market by going to college, enrolling in training programs or otherwise sitting on the sidelines. Add them back in, and the unemployment rate for Americans under 25 would be over 20%.

The median weekly wage for young workers has fallen more than 5% since 2007, after adjusting for inflation; for those 25 and older, wages have stayed roughly flat.

This generation’s struggles have few historical precedents, at least in the U.S. The recession of the early 1980s was comparable but was followed by a rapid recovery. The economic legacy of the Great Depression was erased to a large degree by World War II and the boom that followed. No similar rebound looks likely this time around.

What evidence does exist suggests today’s young people will suffer long-term consequences.

Mr. Wetherell has noticed that more and more of his co-workers have college degrees, some from well-regarded colleges like Washington University. What he had intended as a job to help pay his way through college has now turned into a destination for college graduates.

Americans aren’t the only ones asking such questions. The financial crisis that began in the U.S. quickly rippled across the Atlantic, bursting similar credit and property bubbles in countries such as the U.K., Ireland and Spain, and crippling a European banking sector that had dense links.

Americans aren’t the only ones asking such questions. The financial crisis that began in the U.S. quickly rippled across the Atlantic, bursting similar credit and property bubbles in countries such as the U.K., Ireland and Spain, and crippling a European banking sector that had dense links.

In the U.K., whose financial fortunes mirrored the U.S.’s closely, so many young people have been pushed to society’s shadows that they have their own name—NEETs—for “not in education, employment or training.” Their existence has helped to fray the social fabric not only in London, but places like Athens and Stockholm. Those cities have seen riots led by young people who have become alienated from political and economic institutions that no longer seem to offer hope of prosperity.

The U.S. has thus far escaped such turmoil. Polls show young Americans remain generally optimistic about their long-term future, even as they remain pessimistic about their immediate prospects.

But there are signs that the weak economy is leading to deep societal changes. An entire generation is putting off the rituals of early adulthood: moving away, getting married, buying a home and having children. The marriage rate among young people, long in decline, fell even faster during the recession, and the birthrate for women in their early 20s fell to an all-time low in 2012. According to a recent Pew Research study, 56% of 18- to 24-year-olds lived with their parents in 2012, up from 51% in 2007—an increase that looks particularly dramatic because the share had changed little in the previous four decades.

The costs of a “lost generation” go beyond the impact on young people themselves. A 2012 analysis commissioned by the Corporation for National and Community Service, a federal agency, estimated that the 6.7 million American youth who are disconnected from both school and work could ultimately cost taxpayers $1.6 trillion in lost tax receipts, increased reliance on government benefits and other expenses. Look at broader economic and social effects such as lost earnings and increased criminal activity and the impact tops $4.7 trillion, the researchers estimated.

Moreover, many college graduates face an added challenge that was far less common in earlier generations: mountains of student debt. Even as mortgage and consumer debt plunged in the wake of the financial crisis, student loan balances nearly tripled from 2004 to 2012, to roughly $1 trillion, according to a recent study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. More than 40% of 25-year-olds now hold at least some student debt. The average borrower owes roughly $25,000.

The rising level of student debt, especially during a period of poor job opportunities, is likely to have long-term consequences. A recent study from the left-leaning think tank Demos estimated that $53,000 in student debt—the average debt burden for a household with two college graduates—will reduce lifetime wealth by more than $200,000.

Emily Koehler, a friend of Mr. Wetherell’s, graduated from the University of Missouri-St. Louis and hoped to go into public policy or the nonprofit sector. Instead, Ms. Koehler is doing clerical work for $15 an hour.

Ms. Koehler says she is less worried about the present than the future. She says she can’t imagine when she’ll be able to afford a house or children. “You don’t dream big,” she says. “You’re always checking yourself, or you don’t even think about doing other things anymore.”

More From The Wall Street Journal (subscription required):