The Nordic Glass Ceiling

< < Go Back

By Nima Sanandaji,

The Nordic countries are widely regarded as world leaders in gender equality. In the Global Gender Gap Index, the Nordic nations are top performers. Iceland leads the list, followed by Norway, Finland, and Sweden in second, third, and fifth places, respectively. Denmark ranks lowest in 14th place, but still considerably higher than the United States, which is in 49th place.

A common view is that Nordic gender equality reflects the social welfare policies of these nations. Indeed, Nordic governments advertise their welfare systems as a recipe for gender equality and even promote these policies in the United States for that reason. Several other European countries have followed in Norway’s tracks by legislating gender quotas for board of director positions in publicly traded firms. Although the political climate in the United States is not ripe for quotas, that policy does lie on the horizon.

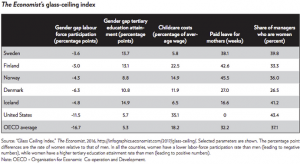

This analysis argues that gender quotas have been ineffective and that several aspects of Nordic social policies have negatively affected women’s career progress and even contributed to a glass ceiling. The glass ceiling is a metaphor for the barriers women face in reaching leadership positions.

While Nordic societies are indeed role models when it comes to gender equality, this equality stretches back centuries before the modern welfare state and reflects traditional Nordic culture.

The Nordic countries are in many ways the most gender-equal in the world, owing to their history, culture, and some beneficial policies. Therefore, foreign observers assume replicating Nordic policies is the key to women’s progress, even when facts and research tell us the opposite.

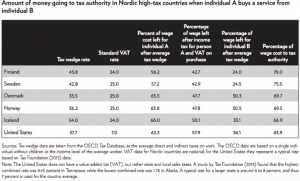

Welfare policies, high taxes that make it costly to purchase substitutable services, generous benefit systems that reduce economic incentives for full-time work, public-sector monopolies/oligopolies in female-dominated sectors, and paid-leave policies that incentivize long breaks from working life prevent women from reaching the top. Taken together, these policies create a Nordic glass ceiling. Gender quotas are unable to make up the difference, even though politicians routinely point to gender quotas as a policy success story. In reality they fall short of their objectives.

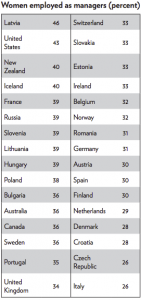

It is true that Nordic countries have high female employment rates and an unusually gender-equal history and gender-equal values, and these achievements merit admiration. Still, the proportion of women managers, executives, and business owners is disappointingly low. Several other countries that lack the advantages of the Nordics, but have more small-government and market-oriented policies, have a larger proportion of women who reach the top. This is true of the United States. The Nordic Gender Equality Paradox is important to keep in mind in countries such as the United States, where Nordic-style welfare policies are routinely touted as a way of promoting gender equality without tradeoffs.

The pattern within the Nordics is also worth keeping in mind. More women reach executive positions in Iceland, the Nordic country with a smaller welfare state, than in Denmark, the Nordic country with an unusually large welfare state. This pattern, together with various studies cited in this report, suggest that key aspects of social welfare policy hold professional women back.

More From CATO Institute: