Ex-CIA Directors: Interrogations Saved Lives

< < Go Back

The Senate Intelligence investigators never spoke to us—the leaders of the agency whose policies they are now assailing for partisan reasons.

The Senate Intelligence Committee’s report on Central Intelligence Agency detention and interrogation of terrorists, prepared only by the Democratic majority staff, is a missed opportunity to deliver a serious and balanced study of an important public policy question. The committee has given us instead a one-sided study marred by errors of fact and interpretation—essentially a poorly done and partisan attack on the agency that has done the most to protect America after the 9/11 attacks.

Examining how the CIA handled these matters is an important subject of continuing relevance to a nation still at war. In no way would we claim that we did everything perfectly, especially in the emergency and often-chaotic circumstances we confronted in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. As in all wars, there were undoubtedly things in our program that should not have happened. When we learned of them, we reported such instances to the CIA inspector general or the Justice Department and sought to take corrective action.

The country and the CIA would have benefited from a more balanced study of these programs and a corresponding set of recommendations. The committee’s report is not that study. It offers not a single recommendation.

Our view on this is shared by the CIA and the Senate Intelligence Committee’s Republican minority, both of which are releasing rebuttals to the majority’s report. Both critiques are clear-eyed, fact-based assessments that challenge the majority’s contentions in a nonpartisan way.

What is wrong with the committee’s report?

First, its claim that the CIA’s interrogation program was ineffective in producing intelligence that helped us disrupt, capture, or kill terrorists is just not accurate. The program was invaluable in three critical ways:

• It led to the capture of senior al Qaeda operatives, thereby removing them from the battlefield.

• It led to the disruption of terrorist plots and prevented mass casualty attacks, saving American and Allied lives.

• It added enormously to what we knew about al Qaeda as an organization and therefore informed our approaches on how best to attack, thwart and degrade it.

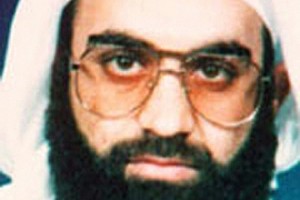

A powerful example of the interrogation program’s importance is the information obtained from Abu Zubaydah, a senior al Qaeda operative, and from Khalid Sheikh Muhammed, known as KSM, the 9/11 mastermind. We are convinced that both would not have talked absent the interrogation program.

The second significant problem with the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report is its claim that the CIA routinely went beyond the interrogation techniques as authorized by the Justice Department. That claim is wrong.

President Obama ’s attorney general, Eric Holder , directed an experienced prosecutor, John Durham, to investigate the interrogation program in 2009. Mr. Durham examined whether any unauthorized techniques were used by CIA interrogators, and if so, whether such techniques could constitute violations of U.S. criminal statutes. In a press release, the attorney general said that Mr. Durham “examined any possible CIA involvement with the interrogation and detention of 101 detainees who were alleged to have been in U.S. custody” after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. The investigation was concluded in August 2012. It was professional and exhaustive and it determined that no prosecutable offenses were committed.

Third, the report’s argument that the CIA misled the Justice Department, the White House, Congress, and the American people is also flat-out wrong. Much of the report’s reasoning for this claim rests on its argument that the interrogation program should not have been called effective, an argument that does not stand up to the facts.

Fourth, the majority left out something critical to understanding the program: context.

The detention and interrogation program was formulated in the aftermath of the murders of close to 3,000 people on 9/11. This was a time when:

• We had evidence that al Qaeda was planning a second wave of attacks on the U.S.

• We had certain knowledge that bin Laden had met with Pakistani nuclear scientists and wanted nuclear weapons.

• We had reports that nuclear weapons were being smuggled into New York City.

• We had hard evidence that al Qaeda was trying to manufacture anthrax.

It felt like the classic “ticking time bomb” scenario—every single day.

In this atmosphere, time was of the essence and the CIA felt a deep responsibility to ensure that an attack like 9/11 would never happen again.

The committee also failed to make clear that the CIA was not acting alone in carrying out the interrogation program.

The CIA went to the attorney general for legal rulings four times—and the agency stopped the program twice to ensure that the Justice Department still saw it as consistent with U.S. policy, law and our treaty obligations. The CIA sought guidance and reaffirmation of the program from senior administration policy makers at least four times.

We relied on their policy and legal judgments. We deceived no one.

The CIA briefed Congress approximately 30 times. Initially, at presidential direction the briefings were restricted to the so-called Gang of Eight of top congressional leaders—a limitation permitted under covert-action laws. The briefings were detailed and graphic and drew reactions that ranged from approval to no objection. The briefings held nothing back.

Congress’s view in those days was very different from today. In a briefing to the Senate Intelligence Committee after the capture of KSM in 2003, committee members made clear that they wanted the CIA to be extremely aggressive in learning what KSM knew about additional plots. One senator leaned forward and forcefully asked: “Do you have all the authorities you need to do what you need to do?”

In September 2006, at the strong urging of the CIA, the administration decided to brief full committee and staff directors on the interrogation program. As part of this, the CIA sought to enter into a serious dialogue with the oversight committees, hoping to build a consensus on a way forward acceptable to the committee majority and minority and to the congressional and executive branches. The committees missed a chance to help shape the program—they couldn’t reach a consensus. The executive branch was left to proceed alone, merely keeping the committees informed.

How did the committee report get these things so wrong? Astonishingly, the staff avoided interviewing any of us who had been involved in establishing or running the program, the first time a supposedly comprehensive Senate Select Committee on Intelligence study has been carried out in this way.

The excuse given by majority senators is that CIA officers were under investigation by the Justice Department and therefore could not be made available. This is nonsense.

We can only conclude that the committee members or staff did not want to risk having to deal with data that did not fit their construct. Which is another reason why the study is so flawed. What went on in preparing the report is clear: The staff picked up the signal at the outset that this study was to have a certain outcome, especially with respect to the question of whether the interrogation program produced intelligence that helped stop terrorists. The staff members then “cherry picked” their way through six million pages of documents, ignoring some data and highlighting others, to construct their argument against the program’s effectiveness.

In the intelligence profession, that is called politicization.

It’s fair to ask whether the interrogation program was the right policy, but the committee never takes on this toughest of questions.

On that important issue it is important to know that the dilemma CIA officers struggled with in the aftermath of 9/11 was one that would cause discomfort for those enamored of today’s easy simplicities: Faced with post-9/11 circumstances, CIA officers knew that many would later question their decisions—as we now see—but they also believed that they would be morally culpable for the deaths of fellow citizens if they failed to gain information that could stop the next attacks.

Between 1998 and 2001, the al Qaeda leadership in South Asia attacked two U.S. embassies in East Africa, a U.S. warship in the port of Aden, Yemen, and the American homeland—the most deadly single foreign attack on the U.S. in the country’s history. The al Qaeda leadership has not managed another attack on the homeland in the 13 years since, despite a strong desire to do so. The CIA’s aggressive counterterrorism policies and programs are responsible for that success.

More From The Wall Street Journal (subscription required):