Xi’s Power Play Foreshadows Historic Transformation of How China Is Ruled

< < Go Back

Party insiders say president wants to remain in office after his second term, breaking succession conventions.

China’s Communist Party elite was craving a firm hand on the tiller when it chose Xi Jinping for the nation’s top job in 2012. Over the previous decade, President Hu Jintao’s power-sharing approach had led to policy drift, factional strife and corruption.

The party’s power brokers got what they wanted—and then some.

Four years on, Mr. Xi has taken personal charge of the economy, the armed forces and most other levers of power, overturning a collective-leadership system introduced to protect against one-man rule after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976.

Shattering old taboos, Mr. Xi has targeted party elders and their kin in an antigraft crusade, demanded fealty from all 89 million party members, and honed a paternalistic public image as Xi Dada, or Big Papa Xi.

Now, as he nears the end of his first five-year term, many party insiders say Mr. Xi is trying to block promotion of a potential successor next year, suggesting he wants to remain in office after his second term expires in 2022, when he would be 69 years old.

Mr. Xi, who is president, party chief and military commander, “wants to keep going” after 2022 and to explore a leadership structure “just like the Putin model,” says one party official who meets regularly with top leaders. Several others with access to party leaders and their relatives say similar things. The government’s main press office declined to comment for this article, and Mr. Xi couldn’t be reached for comment.

Mr. Xi’s efforts to secure greater authority may help ensure political stability in the short run, as an era-defining economic boom starts to falter. But they risk upending conventions developed since Mao’s death to allow flexibility in government and ensure a regular and orderly transition of power.

Concern is rising among China’s elite that the nation is shifting toward a rigid form of autocracy ill-suited to managing a complex economy. China’s array of challenges includes weaning the economy off debt-fueled stimulus spending, breaking up state monopolies and cleaning up the environment.

“His dilemma is that he can’t get things done without power,” says Huang Jing, an expert on Chinese politics at the National University of Singapore. “He feels the need to centralize, but then he risks undermining these institutions designed to prevent a very powerful leader becoming a dictator.”

Mr. Xi’s supporters say he still faces resistance within the party, and needs to modernize leadership structures to confront the slowing economy and a hostile West.

At a meeting of 348 party leaders in October that granted Mr. Xi another title—“core” leader—he railed against indiscipline and warned of senior officials who “lusted for power, feigned compliance and formed factions and gangs.”

Since then, many party members have signed written pledges of “absolute loyalty.” In a speech in October, the party chief of Henan province, Xie Fuzhan, hailed Mr. Xi as a “great leader”—words usually reserved for Mao.

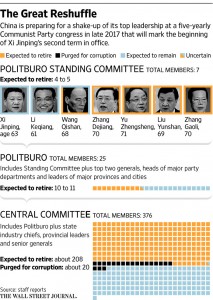

Hours before Donald Trump’s election victory, China officially launched its own convoluted process for selecting a new national leadership team, to be unveiled at a twice-a-decade party congress next fall. Up to five of the seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee, China’s top leadership body, are due to retire.

Only Mr. Xi and Premier Li Keqiang would remain if the party observes the precedent, established in 2002, that leaders over age 67 step down.

Replacements usually are chosen by outgoing and retired Standing Committee members. The custom since 2007 has been that two of those selected are young enough to succeed the party chief when he completes his second term.

“China’s strongest leaders needed at least 20 years to achieve results. Xi Jinping will be the same,” says one retired senior official who has regular access to party leaders. “Mao built the nation. Deng Xiaoping made it rich. We’re now in the Xi era, which will make it strong.”

Mr. Xi’s goal appears to be to remodel the party as a disciplined organization, loyal to him personally, and to reassert its role as the dominant force in society and the economy. He believes in top-down decision-making by a small circle of advisers, who now govern through a dozen or so committees Mr. Xi heads, party insiders say.

More From The Wall Street Journal (subscription required):