A Shocking Internet Attack Shows America’s Vulnerability

< < Go Back

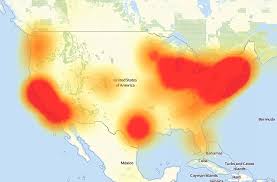

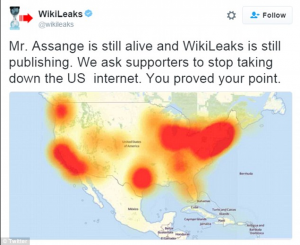

This heat map highlights the extent and severity of Internet outages during the Oct 21 cyberattack.

The Internet began to wobble at 7 a.m. Early on Oct. 21, servers at a little-known Internet infrastructure company, Dyn, based in Manchester, N.H., began experiencing an overwhelming flood of malicious traffic. By midday a coordinated series of attacks had metastasized, eventually blocking or significantly slowing access to dozens of sites, including Twitter, Netflix, Spotify and Airbnb, for millions of Americans as well as web users in Brazil, Germany, India, Spain and the U.K. The FBI and the Department of Homeland Security are looking into the attack, thought to be the largest of its kind ever. But by the time the disturbance ebbed the following day, the point security researchers have been making to one another at an increasingly alarmed pitch in recent months became clear to a much broader public: America’s digital infrastructure is deeply vulnerable.

As has become the norm with cyberattacks, the how became apparent long before the who or why. (Experts don’t believe a nation-state sponsored the strike; a collective that calls itself New World Hackers claimed responsibility, without proof, on Twitter.)

What was most shocking about the latest assault were the tools used to mount it. Hackers employed a vast array of remotely controlled Internet-connected gadgets–surveillance cameras, printers, digital video recorders–to generate the crippling deluge. They exploited these devices, which are part of the so-called Internet of Things and often suffer from weak or nonexistent security, thanks to a virus called Mirai. Internet provider Level 3 Communications estimates Mirai has infected some 500,000 gadgets. Experts call this phalanx of zombie devices a botnet army. And by one estimate, just 10% of the Mirai army was deployed this time.

The Internet of Things is growing faster than government’s or industry’s ability to secure it. There are now 6.4 billion connected devices globally, according to researcher Gartner. By 2020, that will balloon to 20.8 billion.

Consumers can protect themselves to a degree by keeping the software on their devices updated or changing the default password if possible. But most cyber researchers say device manufacturers must be held responsible for better security. How to do that remains unclear, though legislation may be coming: on Oct. 24, Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson seemed to suggest as much, saying his department would produce a strategic plan “in the coming weeks.”

What could a more damaging event look like? Denise Zheng, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic & International Studies, says it might target health care or the financial realm. Or as several security experts warned, hackers could attempt to disrupt the U.S. presidential election by hobbling state and county election websites. Since voting machines are not connected to the Internet, it would be difficult to undermine the vote itself. But they could easily create an impression to the contrary.

Indeed, opacity and uncertainty are shaping up to be defining features of the cyber era. There is another telling detail about this attack: the Japanese word mirai translates as “the future.”

More From TIME Magazine: